The grocery segment is grappling with the same profitability concerns as the restaurant space as delivery continues grabbing a larger share of the pie. Consulting firm McKinsey explored the challenges and opportunities in a new report on the grocery industry, making a strong case for new models and deeper technology penetration.

Authors John Barbee, Raoul Dubeauclard, Kyle Jensen and Julia Spielvogel, all partners and consultants at the firm, laid out the problem succinctly.

“While omnichannel continues to offer added convenience for consumers, profitability remains a challenge for grocery retailers,” read the report.

Costs of delivery for grocers runs from 10 to 14 percent as a percentage of sales. That’s lower than the restaurant business sees overall, but in an industry that carries slimmer margins. On average, the grocery industry brings home a 2-3 percent profit margin, which is half or less than the restaurant space. Those fundamentals make digital change a different beast, requiring both greater scale and lower investments as a percentage of sales.

There are a few key things that the industry is thinking about: delivery windows, assortments of products (SKUs) and accuracy. All need to match both the consumer desire for convenience and the economics of the business.

1. Right-sizing the delivery window

Instant or scheduled delivery is one of the bigger questions out there today. The instant players like Gorillas or Buyk cater to one end, while traditional grocers trend toward larger, more expensive orders. Researchers found that consumers wanted a specific order window more than lightning-fast delivery.

“A narrow window creates little room for error or to flex shipments for the most efficient routes. However, too broad of a window could lead consumers to choose another retailer,” read the report. “Indeed, research on U.S. consumer willingness to pay indicates stronger preferences toward precise windows versus faster delivery.”

2. SKU load balancing

Does a grocery delivery operation offer tens of thousands of items in a typical grocery store or does it limit what it offers? The latter is how instant grocers keep things simpler, but consumers want options and convenience.

“A broader assortment includes trade-offs on available space to store a longer tail, the accuracy of inventory (and subsequent impact on picking efficiency), and the productivity of operations when fulfilling large, complex orders,” read the report.

3. Keeping up with stock

Hand in hand with SKUs is product availability. Supply chains are highlighted these days, but it’s a perennial problem in the grocery space. Report authors looked to data from grocery data provider IRI.

“According to IRI’s latest CPG Supply Index, 11 percent of edible packaged consumer products will be out of stock in store. In a pick-from-store model, this means 10 to 15 percent of orders will experience stockouts and potentially require substitution during fulfillment,” read the report. “One-to-one engagement significantly reduces order-picking productivity but provides a premium service.”

Imperatives for the omnichannel grocer

McKinsey authors laid out three key ways to address those challenges.

Grocers looking to make sense of omnichannel opportunities need to optimize for the use cases in front of them, make operators more efficient and overlay the last-mile logistics on top. No problem, right?

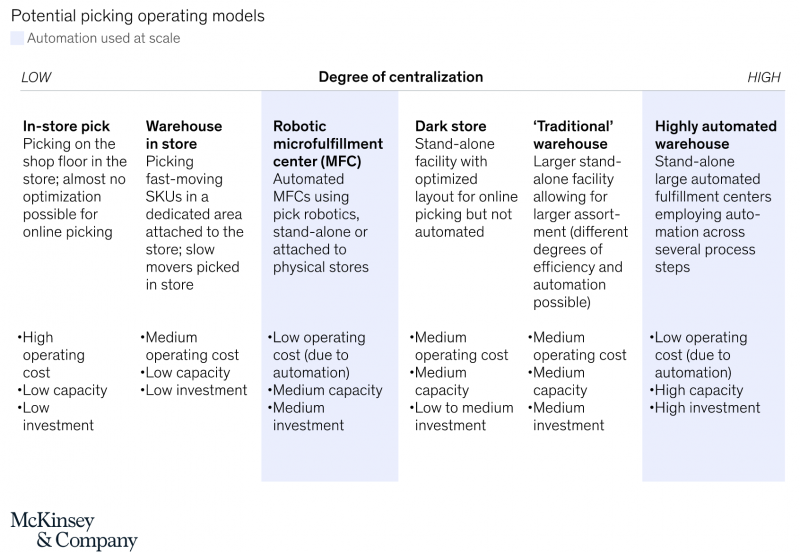

Authors looked at how European grocers Tesco and Ocado Group optimized with a mix of “traditional stores, dark stores, microfulfillment centers (MFCs), and highly automated central fulfillment centers (CFCs).”

Tesco used a mix of all, and its launching 10 MCFs over the next 10 years to compliment traditional stores where picking products is vastly more time consuming. Ocado announced it would build 56 CFCs to ensure fewer stock issues across the supply chain. Walmart announced plans to scale MCFs inside their existing locations.

“In many cases, these MFC models play a specific role in high-density areas to augment pick-from-store volume,” read the report.

There’s a lot to think about here, as shown in the rubric below.

Not included in the report were all the instant grocery players who have made the MCF model a core competency. It seems clear that smaller, exceptionally efficient approaches to the mindless drudgery of picking is the only solution to instant delivery and make all orders more efficient.

To further optimize the business, the industry looks to make that process even more efficient. Picking for multiple orders and smarter analytics around labor are both top of mind. The former is an easy way to be more efficient with picking, the latter helps grocers better measure the workforce doing the picking for further efficiency tweaks.

Better analytics around substitutions is also a key focal area so pickers don’t have to interrupt their work to chat with customers or get them something insane like dairy-free ice cream as a logical substitution to out-of-stock, real ice cream. [Editor’s note: this actually happened to me and it will haunt me forever.]

There is some interesting potential with real-world technology. The report looks at one way operators might really boost efficiency with “pick to light with electronic shelf tags” i.e., a visual cue for pickers to find their items.

“In an in-store picking environment, the pick path and search efficiency are often only as good as a picker’s experience and the clarity of images provided on their handhelds. With the introduction of electronic shelf tags, their illumination can improve search and picking efficiency, much like the pick to light used in warehouse settings,” read the report.

One can see the potential for a real-world game of Pac-Man where pickers zip from one light to another, cutting search times in a traditional grocery store to something akin to a MCF.

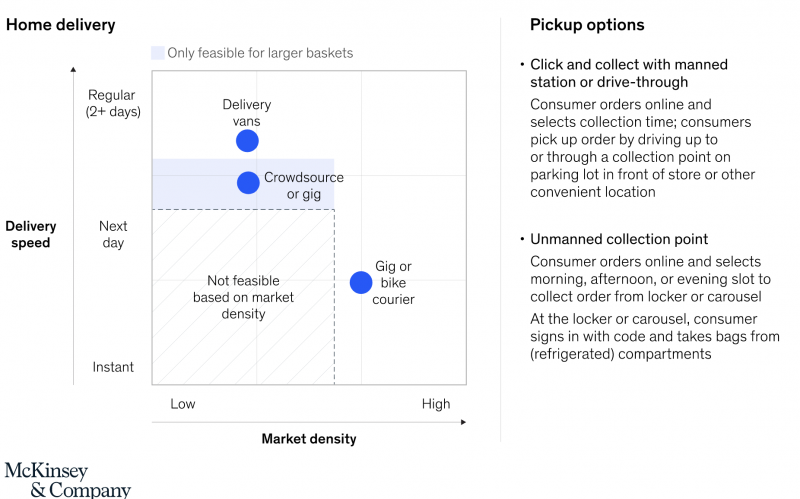

Then there’s the question of last-mile logistics, which evolves minute-by-minute. Drones, in-house fleets, and outsourcing to gig workers are all on the table. They’re also exceptionally expensive ways to meet consumer demands.

“Flexibility in delivery time windows allows for more efficient routes by combining several deliveries in a milkman run. However, fixed, narrow time slots lead to suboptimal routing and possible wait times, potentially increasing costs by more than 100 percent,” read the report.

There are plenty of models, but the rubric below shows that they don’t all work everywhere.

Authors looked at what Dutch grocer Picnic did. Much like Club Feast looks to do in the restaurant space or Amazon has done with everything else, Picnic requires customers to order ahead to enable planned routes.

“The retailer increases efficiency through a targeted assortment and a milkman-run approach, where electric delivery vehicles visit a given area just once or twice a day to increase the density of last-mile deliveries,” read the report. “This allows Picnic to optimize routing plans while limiting service restrictions.”

The full report holds a lot of interesting nuggets to think about in the grocery space, and foreshadows a lot more innovation to come. It does highlight how traditional grocers are struggling to catch up with the explosive growth of instant grocers who have a purpose-built design and quite a lead in technology.