JoyRun, the novel delivery service that takes advantage of community interaction, is moving its national launch up partially because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The company, which started on college campuses before expanding to military bases and a handful of corporate campuses in the Bay Area, offers a different approach to food delivery. In the original model, someone—generally a student in a dorm—would start an order for that proverbial burrito. The JoyRun app sends out a notification to nearby users, allowing them to join the initial order. The app also allows people to request a run, seeking a less lazy nearby user to take orders and do the legwork for a small fee. It was all community driven, so there’s no delivery fleet to maintain or complex algorithmic operations to build. Folks making the delivery could opt to charge a few dollars per order or forgo payment in return for some karma

For restaurants, it’s a little more economical, as well. The commission is typically between 15 and 18 percent, and each JoyRun order is often much larger. As for the “runners,” they tend to see their fee as a discount on a meal, not income. That means there isn’t the drive to tack on delivery fees or increase delivery pay.

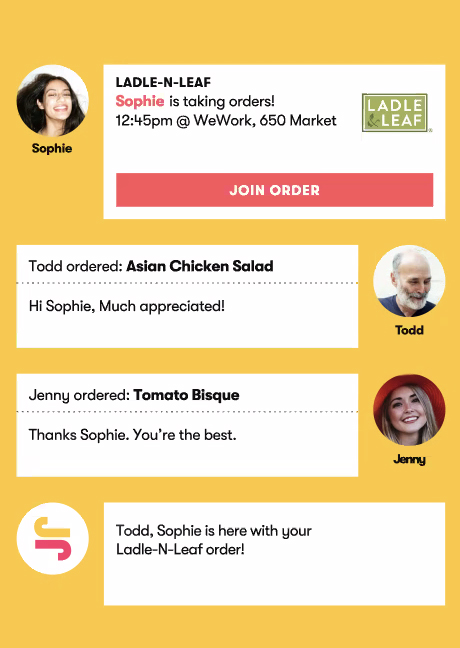

An image from the app showing an example JoyRun order.

“Sophie (for example) can also charge a small fee. She can say, if it’s people in my office I won’t charge, but people outside of the office, maybe they pay $2,” said founder and CEO Manish Rathi. “Sophie gets a discount and the restaurant gets three extra orders.”

But with COVID-19 shutting everything down, Rathi said this accelerated a standing plan for a national launch originally intended for this summer. With the pandemic’s disastrous impact on sales with campuses and businesses shut down, the company saw an opportunity to pivot. Most notably, delivery is spiking while customers are looking for ways to support their favorite restaurants without actually going inside.

He added JoyRun is also seeing dramatic order volume spikes on the military bases it operates on.

“We’ve seen a 30- to 40-percent bump week-over-week in the last seven to eight days as people are more inclined to stay on the grounds,” said Rathi. Even campus-adjacent restaurants, he said, have seen sales upticks through the platform, some doubling sales on the system as faculty and students have remained in the area order more.

The second reason to accelerate the national launch was all the college students whoreturned home to shelter-in-place with family, who have become brand ambassadors, even helping their local restaurants navigate delivery in places that could never support the driver demand necessary for another third-party provider.

“One is a small town in Illinois. There are eight or 10 restaurants, maybe a town of 2,000 to 3,000,” said Rathi. “The restaurants basically stopped doing business, (until) someone said, ‘I’ll act as a delivery service.’ Their thinking was we’ll take orders by phone, but someone told them about JoyRun.”

This change has been quite a learning experience for the company, as well. It has waived commission fees for new restaurants through May, and the team is scrambling to put together tools for operators to make deliveries using JoyRun.

The new volume from JoyRun has helped some restaurants retain front-of-house staff, switching them to delivery drivers, rather than laying them off. That is a key requirement of the Payment Protection Program from the Small Business Administration for businesses that want their loans forgiven.

Restaurants using the platform to do self-delivery on the platform are also batching orders so drivers don’t have to make many small deliveries, which makes them more like a catering order from a logistics perspective. But instead of an individual alerting nearby diners about their order, the restaurant sets up scheduled runs; which alert app users like traditional orders.

One restaurant, Bun Mi in San Francisco, was bringing sandwiches to a hospital as a charity effort. But hospital workers said they could pay and wanted to support the business by paying for sandwiches instead.

“Now, they’re coming at noon and 5 p.m. and doing as many delivery orders that come through the system,” said Rathi. “Instead of one-off orders, they can do these batch orders.”

He said there are only a handful of restaurants—10 to 12—utilizing self-delivery, but he was looking to add more in the days and weeks ahead.

Prior to COVID-19, the company planned to launch nationwide with a handful of key accounts, which was scheduled for when college students already using the service returned home. That’s still planned, but he said this pivot was a way to move things up and help partner restaurants survive through a historically brutal restaurant environment.