Instead of a tired, overworked or maybe even stoned delivery driver, what if your food came from a friendly neighbor, or a happy coworker? That’s exactly the question startup delivery enabler JoyRun seeks to answer by tapping into the delivery gig economy in a way that makes everyone happy—the restaurant, the delivery “runners” and the end users, said founder and CEO Manish Rathi.

Everything comes back to that community-driven aspect from how people order, how influencers in the community drive orders (literally and figuratively) and how local restaurants become more deeply ingrained in the surrounding community.

JoyRun Founder and CEO Manish Rathi

“We think we’re building group delivery for the community by the community. In tech parlance we call it peer-to-peer delivery,” said Rathi. “Every other delivery service is the Uber Black version (expensive), we’re the Uber Pool version. The runner still makes enough money and the buyer still gets a cheaper price.”

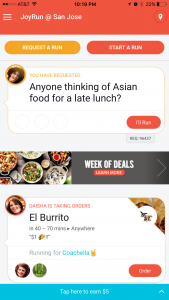

Like Bitorrent—which spawned the peer-to-peer (P2P) nomenclature—JoyRun relies on and encourages people who are already picking up their Lo Mein from the Chinese restaurant up the road to bring a few orders back to their neighborhood. Conversely, runners can announce via the JoyRun app that they’re going for coffee, allowing anyone else with the app to join in the coffee order. And finally, if someone is craving a lazy day of burritos and couch time, they can send out a request for a run that a more-active person can pick up and other couch-potatoes can get in on. In every situation, the runner can opt to charge end customers, or if it’s a friend, just have them pay for their meal—for the karma.

“We’re orchestrating these spontaneous connections between people,” said Rathi.“The community vibes are so strong, you make money, but you also earn social credibility.”

If one didn’t know Rathi is a sharp tech entrepreneur, he might sound like a bit of a hippy. But with a fresh injection of $8.5 million in a Series A on top of $1.5 million in seed funding, he’s not just another sandal-clad dude at the drum circle, his platform actually reflects his pie-in-the-sky rhetoric.

“We’ve raised $10 million so far, to me it’s never a badge of honor, it’s just proof that we’re doing the right thing,” said Rathi.

Doing Third-Party Delivery Different

The main social feed, where “runners” can post and customers can order.

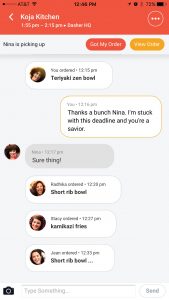

There are four ways Rathi claims JoyRun is different from other third-party delivery services. First is that community connection. Pouring through chat logs, they’ve even seen a few romantic connections, though he said they “definitely aren’t trying to be the Tinder of this industry.”

Second, unlike the Uber Pool, one in five app users has done at least one delivery. If that was the case with Uber, there would be a driver waiting on every corner. Rathi said it brings necessary freedom to the gig economy.

“When you look at the rest of the gig economy world, it’s a job; it’s a flexible job but its still a job,” said Rathi. “We’re enabling everybody to make a little on the side.”

Third, it’s good for restaurants, empowering them to explore delivery without either investing in their own delivery team or signing up for a margin hit with other third-party delivery services.

“We’re enabling every one of their customers to be someone who can bring back food for its customers. So we change the unit economics for delivery. Everybody going in can pick up food for their four friends, quadrupling that check size,” said Rathi. “We’re changing the unit economics of delivery, everybody that is going into the store can bring it back to their friends. It’s truly a win, win, win for the restaurant the runner and the buyer. Our job is to connect those dots.”

It also turns all those runners into cheerleaders for their favorite brands.

“That’s the strongest thing you get, the brand ambassadorship,” he said. For instance, someone might not be thinking about Moe’s Southwest Grill, until someone else says, “I want to get some Moe’s,” and others think, “Oh, yeah I want that, too.”

Ongoing chat between a runner and delivery customers.

That taps latent demand for burritos in the case of Moe’s or coffee from Lazi Cow, an independent coffee shop near the University of California Davis campus. Since JoyRun launched there, 80 percent of Lazi Cow’s delivery orders go through JoyRun. Rathi said its human nature to want something new, and also (first-world) human nature to avoid the decision fatigue of actually choosing something for lunch.

“This is how we live our daily life, were not committed to this and this alone. People want that sense of variation,” said Rathi.

He said when they first experimented with the concept at a former job as a business experiment, it made for some fervent fans of unsung local restaurants.

And finally, people still make money by doing the lifting—even it’s not so heavy.

“On average it’s 40 minutes and they walk way with $15 to do that, it’s pretty phenomenal,” said Rathi. “I wish I could have done that that when I was in college.”

A few have pushed the limits of what it means to gig, earning as much as $1,500 a month. In an article from the San Francisco Chronicle, a number of users said they were able to get more than that average by partnering up on runs and cramming lots of deliveries into a small window. The overall average fee is $3 on the West Coast and $2 on the East Coast, plus occasional tips.

Right now, the app only covers a handful of college campuses. Rathi said they’re following the Facebook approach to rolling out in that regard. Once a few dozen people express interest in having JoyRun, the company opens up on that campus. Next, he said JoyRun will expand into office parks and big business centers in cities where there is already a JoyRun presence to test functionality and prepare it for an even wider audience.