Usually, earnings calls are great information but can have a canned feeling with the droll back-and-forth between management and stock analysts. The latest Grubhub call, however, shed a lot of light not only on company performance during the COVID crisis but also how the company sees the handful of critiques it is facing.

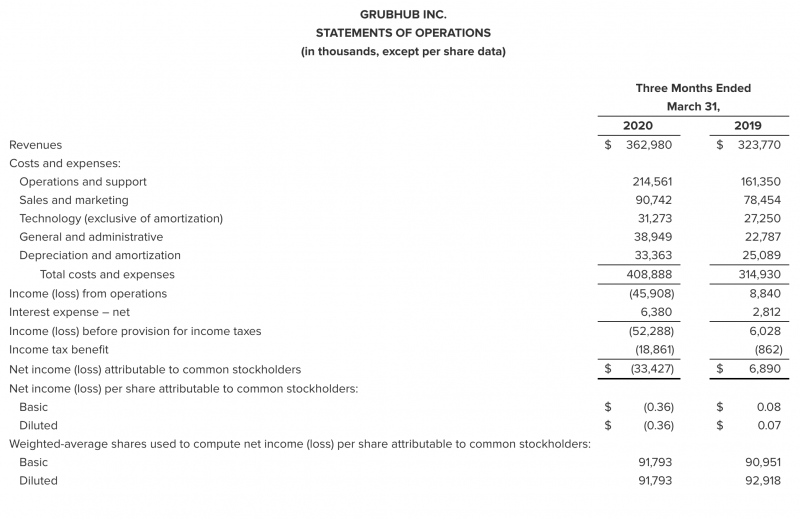

Grubhub ended the first quarter with 23.9 million active diners, up 24 percent year-over-year and up 1.3 million from the fourth quarter of 2019. Food sales were $1.6 billion, which is up slightly from $1.5 billion in Q1 2019. Average tickets for the quarter were $35, up 8 percent. Net revenue was $363 million, an increase of 12 percent over last year. Even so, the company still lost 36 cents per share during the quarter, far from the expected 4 cent loss per share.

Here’s the full account.

Operational costs were up 33 percent to $215 million “driven by the disproportionate increase in Grubhub-delivered orders,” according to the company. Delivered orders were just over 45 percent of dining occasions in the quarter. Overall, that means per-order revenue dipped to $3.16, down from $3.26 in the fourth quarter. Sales and marketing costs increased 16 percent to $91 million; technology expenses were up 15 percent to $31 million. G&A ticked up to $39 million because of a $13 million settlement for “driver misclassification claims,” without that expense, G&A would have been down $1 million compared to the fourth quarter of 2019.

In all, adjusted earnings were $21 million, or 45 cents per order—that’s down from $27 million or 58 cents in the fourth quarter of 2019.

The company ended the quarter with $597 million in cash on hand and it borrowed $175 million in mid-March under a $225 million credit facility “as a precautionary measure given the uncertainty” around the COVID-19 pandemic.

The shareholder letter and earnings call gave a little clarity to the company before and after COVID-19. Generally, the “business was continuing on the same positive trajectory we saw in the fourth quarter due to continued progress across both of our critical strategic initiatives: restaurant supply and loyalty,” according to the letter.

Of course, the quarter was drastically affected by the global pandemic, especially in New York, where Grubhub has a market leading position. When the panic around the outbreak hit, the company “observed a decrease in orders across all of our markets and channels.” That’s something other companies noted and sales-data proved out—scores of people loaded up their pantries and cooked at home. Corporate lunch traffic cratered as people worked from home.

Things began to improve dramatically toward the end of March and into April. The key company metric of Daily Active Grubs (DAGs) was up 20 percent year over year and outside New York many markets were up more than 100 percent.

Founder and CEO Matt Maloney said New York is coming back at encouraging rates, returning to about 75 percent restaurant capacity as some restaurants reopen, but it’s a steady climb.

“It’s harder hit than any other market, we saw the dip to be way larger than anywhere else. We saw this in other hotspots, there’s a dip, a recovery and then an over-indexing. We don’t expect that in New York, but we expect it to recover,” said Maloney on the earnings call.

President and CFO Adam Dewitt said new users have flooded into the system across the country.

“Our new-diner numbers are more robust than the order numbers in March and April. So, we’re seeing millions of new diners try Grubhub for the first time. Then we’re seeing more use cases from our existing diners,” said Dewitt. “People have tried Grubhub in new ways more than they ever have before.”

He said there were more family orders and larger orders that bled across days with people buying dinner and lunch for the next day—part of the company’s promotions. That shift meant much higher ticket averages since COVID-19 hit. New users and higher tickets drove gross food sales dramatically higher.

“At this point last year, we were at about $32 an order; this year it was $40,” said Dewitt. “You’re increasing order size by 25 percent and orders by 25 percent, [so] you’re getting gross food sales close to 50 percent.”

That surge also drove new restaurants to the company, Dewitt said Grubhub is seeing “unprecedented signups” on the independent restaurant side of the industry and Maloney said major enterprise companies jumped on board, too. Everyone from Landry’s (the owner of which also acquired Bite Squad) and Dairy Queen signed on.

“The enterprise brands are really pushing hard to get as many of their locations live as possible. The master service agreement is first, then it’s getting as many franchised restaurants online,” said Maloney.

The non-franchised Chipotle was especially aggressive as it rushed to get online orders within the Grubhub system as it worked through integration.

“We signed Chipotle in the last few weeks and did so on a non-partner basis and are finishing that POS integration as fast as they can,” said Maloney.

As for the macro economy, with more than 33 million unemployed and the potential for a deep recession, that will continue to change things through the second half of the year. Dewitt said he thinks some of the new ordering dynamics will remain, but will be balanced out by the loss of discretionary income and unemployment.

“There’s two arguments there. With less discretionary income, people go to restaurants less. But on the flip side, ordering in is a cheaper replacement for going out. So, I think those balance each other out,” said Dewitt.

What does all this mean for the industry at large? That was a key point of the earnings call and, given the massive influx of people and restaurants, COVID-19 has sped up a lot of the delivery and digital restaurant trends.

“Looking forward, I think one huge takeaway is delivery specifically is front and center for restaurants. It has been growing for the past five years. Every brand has a strategy and a plan they’re looking to adopt,” said Maloney. “With COVID, immediately the bit flipped and delivery and new platforms are here to say. There’s no question about it, it’s a major part of revenue, it’s the sole revenue now but it will remain a major part.”

He said that realization for the restaurant industry and political stakeholders is what is driving activism against the company, the fee caps and the social media campaigns to “delete the apps” for instance.

He said a big misunderstanding for both the industry and the politicians is the fee structure. When people see 30 percent off the topline, as they have in delivery network bills floating around on Twitter, they worry for their local burger spot.

“Restaurants are in a lot of pain. People see their restaurant and they’re worried that they’re going to close,” said Maloney, in a rare discussion of the politics of delivery.

He said that pain has the company eschewing earnings, and reinvesting in marketing to push more sales to restaurant partners, spending an additional $50 million in hopes of driving $150 million in additional food orders.

“We’re bending over backward, deferring revenue giving profitability and doing everything we can imagine to help restaurants. At the end of the day ,the restaurant business is our business. Without restaurants we don’t have a platform,” said Maloney. “It is frustrating to see things that are inaccurate and poorly motivated.”

He said restaurants can utilize Grubhub at varying levels, but also that the economics of running delivery aren’t as obscene as some people think.

“The costs are real. If any platform didn’t deliver, the restaurant would have to pay the $5. That’s expensive, that’s about 20 percent,” said Maloney. “It’s a push and a pull, but unfortunately it’s a crisis situation and these tensions are heightened. So, we’re focused on educating and telling people that we’re part of this important ecosystem.”

He called out competitors for taking a one-size-fits-all approach to fees.

“I think a one-size-fits-all will not work, I think you see a huge amount of frustration and anxiety especially when this industry is the only way to do business,” said Maloney. “Our competitors came in as logistics and charged 30 percent just to deliver. So, you have a pricing model that is not understood frankly by the restaurants or the elected authorities. I think we have the right pricing model. I think all pricing models will ultimately evolve to our platform where executing an online order is a commodity.”

From that commoditized level, he said Grubhub partners choose how to invest, whether it’s paying for advertising, for delivery or access to the corporate infrastructure.

He and Dewitt said the company is taking real measures to help the “ecosystem” overall.

“The EBITDA is not as important right now as supporting our ecosystem. Our restaurants are challenged as their business models have been turned upside down and we’re making a much better use of our cashflow,” said Dewitt. “We think with this spend, we can drive an additional $150-million-plus to our restaurant partners. We think, at this point in time is the right decision.”