The restaurant delivery scene is about to get Trivago-ed. Or Pricelined, Expedia-d or Googled—whatever your favorite industry middleman brand might be. With the great restaurant reshuffle now divided between the two sides of the gym—nervous restaurateurs on one side and cocksure third-party delivery services on the other—FoodBoss is coming in as a neutral party giving customers one single place where they can see which delivery service is offering the best deal in total cost and delivery time, among other filters. The goal is to create an aggregator for meal-delivery marketplaces, just like what’s happened in airlines, hotels, event tickets and prescription drugs.

Following the exact playbook of nationally known, furiously advertised brands that are best known in the travel space, Chicago-based FoodBoss seeks to give consumers an easy, one-stop place to figure out who’s offering the best deal. This gives consumers the ability to still feel somewhat frugal about delivered means, without having to handle the modern-day drudgery of installing apps from your favorite restaurants and delivery services on your phone.

While it’s easy to laugh off this facet of consumer behavior, countless industry analysts have studied customer loyalty between delivery apps and this minutia of consumer behavior translates into big dollars among the delivery brands and restaurants clawing at each other for market share.

CEO Michael DiBenedetto describes his aha moment from his previous life as a consultant working on projects into the night and frequently ordering delivery. That frequency cast a bright light on the fact that hungry consumers didn’t have a single source to look for good delivery deals like what’s out there in so many major industries. This realization came in 2016, and by the end of the year he had a beta version in development.

As the story so often goes in this overlapping space between foodservice and Silicon Valley, FoodBoss soon picked up an investment from Cleveland Avenue, which includes the brainpower (and cash) of former McDonald’s CEO Don Thompson.

“If you look at travel, you look at insurance, you look at tickets, you look at cars, you look at pharmacy—I’ll go through each example—there’s an aggregator that exists in every single category,” DiBenedetto said. The value proposition for the consumer is we show you in real time which service works with what restaurant and what those corresponding total fees are.”

Sticking to the aggregator’s playbook, he said that FoodBoss will never work directly with restaurants, but that restaurants would benefit as its service takes off. Pulling yet another airline analogy out of his back pocket, DiBenedetto said it’s just like how you can see American Airlines selling seats on Expedia or Travelocity, meaning that food is officially the commodity in the great delivery explosion.

“Consumers want to find the cheapest price and the fastest flight times because the seat is a seat,” he added using a multi-unit pizza place in Chicago as an example. “Lou Malnati’s pizza is Lou Malnati’s pizza regardless of who delivers it.”

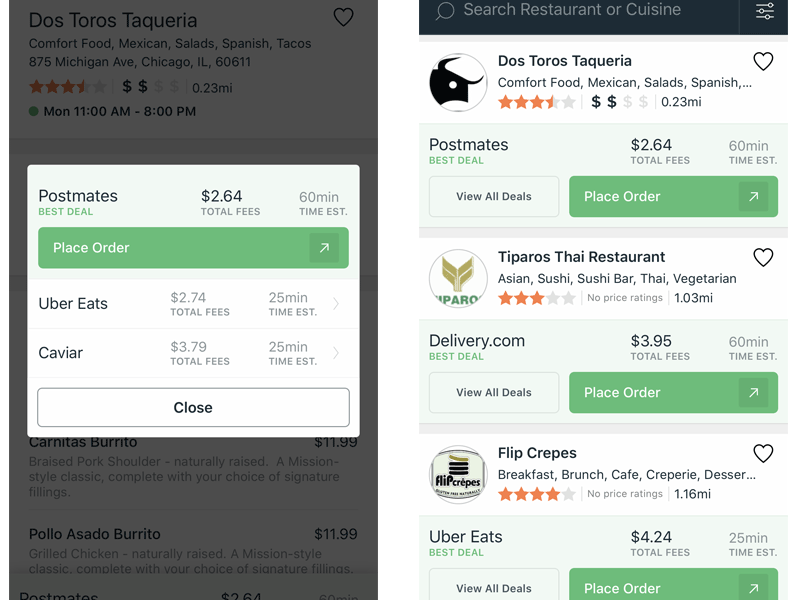

At present, FoodBoss is integrated with Uber Eats, Postmates and Delivery.com, with either Grubhub or DoorDash joining the platform within the next few days. For the delivery brands themselves, often referred to as delivery aggregators, FoodBoss sees them benefitting by bringing clearly hungry, motivated consumers right to their door, allowing them to spend less on broad-based customer advertising channels like the many national TV commercials that have become a fixture over the last year.

It’s here where DiBenedetto uses a lot of keywords that show up in Grubhub and Uber investor calls, especially about the costs for these channels to acquire new customers.

“When you get passed along to our partner site, you’re going to complete that order at a higher conversion rate than other advertising channels that some of our partners advertise with, and that’s the ultimate goal,” he said. If third-party companies get lower tacks with their consumers, the ripped effects go through every part of the industry” including lower fees charged to restaurants.

While that’s a noble goal that will perk up the ears of restaurateurs, there are plenty of other examples to pull from, like airlines not trickling down lower fuel costs to consumers after the oil price shocks of the late 2000s.

DiBenedetto added that, since delivery services have vastly different market shares from one city to the next, being on FoodBoss can elevate their profile in weaker markets by putting their service and offerings right in front of those hungry eyeballs.

“We’re giving them brand awareness and visibility in cities where they might be the No. 1 or No. 2, but consumers still want to see them as an option” without keeping the app on their devices, he said.

FoodBoss sees Google Maps as its primary competition, with new features like the Order Now button giving its users the ability to directly place orders from search pages. Rather than being scared off by Google and its endlessly deep pockets, DiBenedetto said seeing such a massive player enter the space creates “huge market validation” of their own playbook. Of course, it’s also very likely that additional meal-delivery aggregators spring up, especially as the delivery brands continue escalating their customer acquisition spending to boost their own numbers.

With aggregators being almost exclusively marketing-based companies with some software engineers on the side, it’s very likely that Food Boss will be on the receiving end of additional investment rounds to fuel its nascent national advertising machine.

Having installed the app and tried it out, it lists estimated delivery time, total fees and a little tag showing “best deal” for the particular restaurant you’re jonesing for. Compared to the biggest delivery brands, the offerings still include plenty of franchises, but anecdotally felt like it had more independent restaurants than Uber Eats, DoorDash or Bite Squad in the Minneapolis market. Consumers appear to enjoy the offering, with a 4.8-star rating on the Apple App Store.

Comparing the prospects for the food delivery aggregating scene in comparison to similar travel providers, DiBenedetto stressed that even though individual restaurant orders are smaller than buying a family-sized pack of plane tickets, it’s the frequency of eating over air travel that makes this new sub-industry an even bigger fish.

“The cart size might be smaller on food delivery, but the volume is significantly higher,” he added. “When you look at travel versus food, you’re spending more in a given year for food delivery than you are on travel purchases, because a typical family only travels once per year but the average consumer orders food one-and-a-half times per week.”