By Nicholas Upton

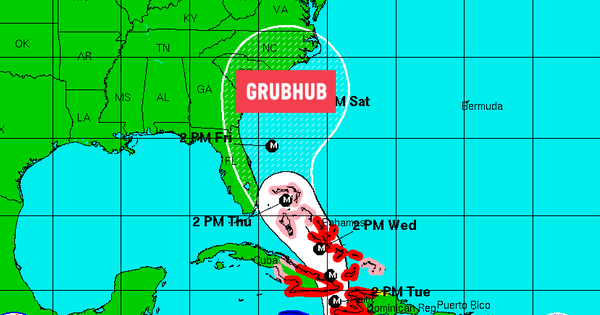

Whenever a hurricane comes along, meteorologists love to make a big map with lots of scary red lines showing where the storm might go. What’s been dubbed “the cone of uncertainty” has everyone up and down the coast glued to the television until—most often—the hurricane loses steam and disintegrates in the Caribbean

Right now, GrubHub has a wide cone of uncertainty ahead of it. Will it make landfall, blowing away rivals and storming the restaurant-delivery landscape? Or will it come to pieces between high-pressure rivals of Uber and Amazon?

The company released its earnings on February 8, and it was a good quarter and pretty good year for the company. Revenue was up 36 percent in 2016, reaching $493.3 million. Net income grew 30 percent to $49.6 million. The company counted 8.17 million active diners—a key metric for the sticky third-party delivery companies—that’s up 21 percent over 2015. And the diners ate out in nearly equal proportion, what the company calls Daily Average Grubs rose 21 percent as well. Overall, $3 billion in gross food sales flowed through the system, a 27 percent increase from 2015.

Despite the solid growth, the results missed estimates from Wall Street, earnings per share came in at 23 cents at $137.5 million for the fourth quarter, a penny shy of an estimated 24 cents and $137.6 million. That sent the stock down precipitously, but stock performance and company performance are two different things. The majority of analysts covering the stock suggest buying the stock, and there are about half that many who suggest holding on to see what happens.

While stock performance isn’t the entire picture of business performance, especially among companies with high valuations like GrubHub at 44 times forward earnings, but there are factors that will guide both the stock and the company in the years to come.

The Bull Case

What might be the path for GrubHub to become leader in third-party delivery? Well, if projections from the company are correct, it’s on the right track.

The company enjoys a 10 to 15 percent market share of the current delivery market. While delivery is just about 5 percent of the market not including pizza delivery, that’s a significant lead over Amazon and Uber.

After a big push of investments mid-2016, the company expects investments expenses to shrink.

“That investment while it was costly, is opening up market opportunities that the company didn’t have before when it didn’t offer delivery,” GrubHub CEO Matt Maloney said during the most recent earnings call. “Penetration in smaller markets where competitors have yet to enter could keep the company ahead of the pack, maintaining an advantage markets just starting to grow third-party delivery. Delivery has opened up conversations with both chains and independent restaurants that we could not have before.”

GrubHub reached corporate-level agreements with Red Robin Gourmet Burgers, Denny’s, Hooters, and Einstein Bros. Bagels, while increasing coverage with existing partners, such as Buffalo Wild Wings, Subway and P.F. Chang’s.

The stickiness of users in the delivery market is key for the bull case. According to research from McKinsey, delivery firms enjoy an 80 percent customer retention rate. So if the company can continue growing users 20 percent year-over-year, it will be well positioned for the ongoing cash flow necessary for investments and growth.

And now the Bear Case

Analysts at Barron’s and elsewhere, however, have a different view. Barron’s released a grim outlook for the company that projected shares to slide significantly as competitors nip at the market leader’s heels.

“The combination of increased competitive and cost pressures could damp financial results, and send the stock down over 25% in the next year or so,” wrote Barron’s Vito Racanelli.

Typically, when a market leader sees nascent competition, it can either put its capital to work to pull further ahead or just buy the competition. But when the competition is Amazon and Uber, those options just aren’t viable.

And what’s worse than having billion-dollar unicorns breathing down your neck is that they have no qualms about profit. Each have such major revenue streams that they don’t even bother to break out their delivery efforts.

Location concerns are also significant. According to Barron’s, 70 to 75 percent of GrubHub’s orders are still in New York and Chicago where restaurants do their own deliveries among the dense-urban cores. That means despite the company’s lead in market share, further expansion means investment in the expensive last mile of delivery.

Last year, GrubHub spent $155 million acquiring four delivery providers in Los Angeles, Boston and Philadelphia. But it’s not the only one bidding on these companies; Caviar bought its way into the Philadelphia market as well. The big dogs are investing too.

“They both said that they’re going to start investing to take advantage of the opportunity, that’s bad news for profitability,” said Howard Penney, a restaurant analyst at Hedgeye Risk Management. “When you’ve got two guys that don’t care about making money competing with a guy in the marketplace that makes money, you know how this is going to end.”

Penney said the companies’ guidance on minimal investment is a mistake and future investments in both delivery and technology are going to be very costly.

“They’re behind the curve, they’re way behind the curve on investing,” said Penney.

As GrubHub works to penetrate smaller markets, the cost of delivery will go up. Drivers only can make limited trips, and commuting customers are less apt to order delivery.

Also unlike Uber or Amazon, which have an army of engineers and developers behind the scenes, GrubHub has had to hire a team of 40 external developers to push the platform to the next level.

Penney said Grubhub is spending money on the wrong side of the delivery equation too, saying that the number of unique diners is only part of the picture despite how sticky users in the space are.

“They’re spending money to acquire customers when they should be spending money to acquire restaurants, they’re not focused on the right things,” said Penny. “Without the restaurants and an attractive proposition for them, who cares how many diners you have. They’re going to go where the restaurants are.”

He points to DoorDash and Postmates, which both have many more restaurant brands under their respective delivery umbrellas.

Marketing costs are also expected to rise, jumping $20 million to $30 million and further eating away at profitability.

So where does this leave the company? Only time will bring clarity to the cone of unpredictability.

Grubhub was invited to discuss the recent earnings but was unable to respond by press time.