A delivery-focused upstart out of New York City claims it has cracked the code to get restaurants the details of who is ordering their food via third-party delivery services, and it’s building a business on helping restaurants market directly to Grubhub, DoorDash, Uber Eats and Postmates customers who order through those popular apps. The company, Bikky, aims to improve the economics for the restaurant industry at a time when there are no financial squares to spare.

Bikky – CEO – Abhinav Kapur

CEO Abhinav Kapur founded Bikky in 2017 after years of working on Wall Street and, before that, working inside the FDIC during the financial crisis. Combining an equity analyst’s perspective with that of his parents’, who run the Amma restaurant in midtown Manhattan, and have used brutally manual tactics to identify and contact third-party delivery customers.

Referencing a specific day when he visited his mother at Amma, Kapur said “she was in the back of the restaurant staring at her Grubhub tablet and scribbling in a notebook, and I was like, ‘What are you doing?’ She said, ‘I recognize that customer’s name and phone number, so I need to give them a call and see how the delivery went.’”

At that pre-COVID-19 point, delivery comprised 30% of Amma’s overall business. Impressed by his mom’s tenacity—down to recognizing customer phone numbers—Kapur set out to “de-anonymize these delivery customers” so restaurant operators could reduce their reliance on third-party delivery services that charge commission rates many restaurant operators call unsustainable.

In a conversation with Food On Demand about the origins of the business, Kapur said he and his team rode around New York City on bikes making deliveries during the development process to learn more about the business. Going to the same buildings over and over, they realized the majority of third-party customers were repeat guests. That meant restaurants need to find creative ways to market directly to those users.

The next big realization came from understanding that single- or several-unit restaurant groups often lacked the manpower to track and analyze customer transactions, especially those coming through ordering platforms that don’t freely share customer data with restaurants.

Without divulging his company’s methods for gathering that data, Kapur said Bikky has “developed ways” to ascertain a third-party customer’s basic data, which restaurants can use to contact those guests and convert them onto first-party channels.

Using the example of Dos Toros, a fast-casual Mexican chain in New York, he said guest targeting can include sending out offers for $10-off native delivery orders or other personalized programs that he claimed can deliver an impressive return on investment (ROI) for operators.

“We basically gave them a list of all their likely third-party delivery customers over the last four- or five-month timeframe, they retargeted them on Facebook, [they] spent $700 over a five-week period … and it generated around $9,000 in direct-ordering revenue,” Kapur said. “So, we’re looking at, essentially, over a 10x ROI on converting customers from third-party to first-party delivery.”

Because marketing can be such a labor-intensive operation for restaurants, Bikky focused its product development on restaurants in the five- to 50-unit size range—establishments that tend to have at least one person on the marketing team, rather than the owner or GM who presumably has bigger fish to fry.

While the driving force of restaurants building native delivery platforms is clearly economic, Kapur sees this “save the restaurants” momentum as a silver lining for the restaurants that find a way to survive this crisis. Beyond that, knowing more about a restaurant’s delivery customers makes it easier for brands to further segment their customer marketing and offer promotions tailored to specific users, rather than their entire customer bases.

A way to use that to tell the customers every business is fighting over is to say, “if you really want to support this industry and you really want to save those businesses, and you really want to treat food as an experience rather than an efficient transaction, then the best way to do that is to order directly from your local favorite,” Kapur added.

Like a few other delivery-focused upstarts, Bikky is using its own content to lure restaurant operators with online pieces like “WTF is a Restaurant CRM?” and “The PPP is Confusing AF (especially for restaurants).”

Further reducing the many topics Bikky covers through its blog and client-based Slack channel, Kapur sees four key ways restaurants can convert third-party delivery guests to in-house channels: price, scarcity, loyalty and experience.

In short, price means charging third-party customers more than native delivery diners; scarcity is offering native-only delivery items or deals; loyalty is allowing guests to earn points regardless of what ordering channel they use; with experience being the exciting part.

Kapur said making native delivery a more “artistic expression” could include secret or rotating menus, or even specials like “date night” promotion or family meal bundles many restaurants have been rolling out, which has worked especially well for Mexicue, a new restaurant in New York that has rolled out several delivery-only promotions.

“It comes down to, really, just how well can you replicate the in-store experience,” Kapur said. “If not replicate the in-store experience, replicate that feeling of what being in-store actually means and help the guest recreate that in their home.”

Kapur expects third-party delivery brands to have an ongoing seat at the restaurant table, but that restaurant operators need options to reduce their dependency to protect profit margins that are more strained than ever.

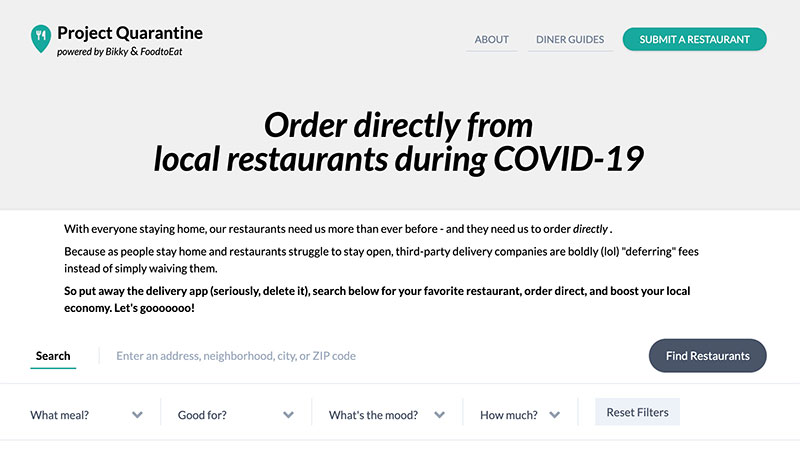

Project Quarantine

When the full impact of the pandemic on the restaurant industry began to wash ashore, Bikky cut subscription rates for its customers by 50 percent and created a Slack channel to keep customers in the loop and share tips and best practices.

While that was helpful and gained traction among their customer base, Kapur said that effort was “still too passive for my liking.” Looking to do more, Bikky worked with an outside developer to build an online aggregator for restaurants that offer direct ordering—even if that’s just phone-based delivery ordering. In four and a half days, Project Quarantine was live with 700 restaurants listed across the NYC metro area. Three weeks later, the effort had expanded to more than 3,000 restaurants in Chicago; Philadelphia; and Washington, D.C., with more cities coming online soon.

With no plans to monetize the service, Project Quarantine users (at eat.bikky.com/) select the meal—breakfast, lunch, dinner, dessert or afternoon delight—occasion, whether that’s individual, “trapped with a roommate” or “full house,” select their price range and then pick out the mood. Mood options include “chillin’ with homies, treat yo self, too cool for school, it’s a family affair, keep grindin’, home comfort, “your body is a temple” or “Oh you fancy, huh?”

Getting back to his parents’ ongoing struggles in the industry, Kapur said “all restaurants want during this time is someone in their corner.” Stressing that restaurant operators did nothing wrong and couldn’t have adequately prepared for this crisis, it comes back to the basic concept that direct ordering will help more restaurants stay in business.

“Everything is couched under one simple premise: What will my mom think?” Kapur said. “I can’t make claims to say we’re saving their businesses, we’re not, but at least we’re doing something that, at least, doesn’t hurt and, at best, helps.”