Wealth management and equity research firm UBS put out a thorough look at the food delivery world and its possible futures. The report, dubbed “Is The Kitchen Dead?” digs into the answers from more than 13,000 consumer surveys and detailed data analysis from apps and industry experts.

Researchers estimate that global online food ordering will grow to $365 billion by 2030, growing 20 percent each year from the $35 billion market seen today.

“Powering this are lower meal production costs, increased logistics scale and strong demographic trends,” wrote the researchers in the report.

Factors that contribute to this include dark kitchens, robot chefs, cheaper deliveries and a generation that cooks far less than others. But the report stops short of calling that one room with the oven terminal. Instead, it lays out two main attributes that will guide the industry: logistics and consumer demand. If logistics and efficiency continue to make things more efficient, prices will go down. If that efficiency is hampered, however, growth will lag. If consumers continue to demand convenient, prepared food, it will still be there in some form. But if they get more interested in cooking, the industry could be challenged.

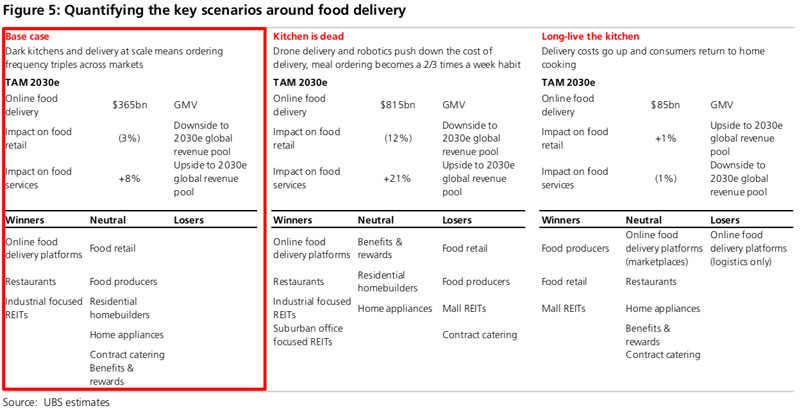

UBS laid out four possible outcomes based on those two foundational attributes. With lower demand, we could see the growth of meal kits or people reverting to traditional cooking. With greater demand, we could be left with either a relatively expensive network of delivery like we currently have or with high efficiency, the death of the kitchen.

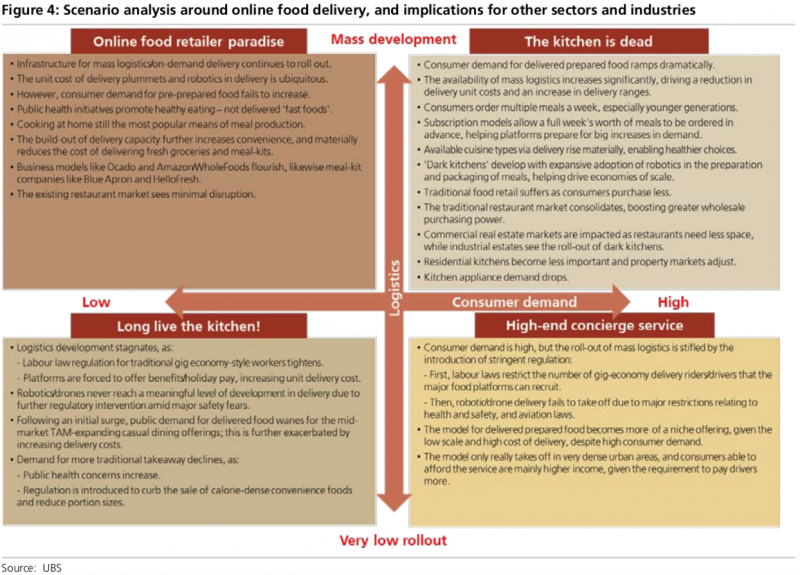

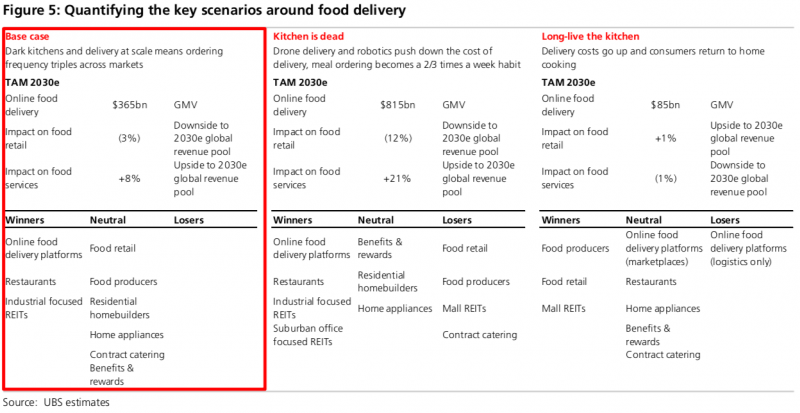

Take a look at a pair of images that outline the possibilities below.

- Figure 4 – Click to enlarge

- Figure 5 – click to enlarge

Because nobody really knows where those foundational attributes will lead the industry, UBS has a few economic scenarios. If things skew toward the high demand and high efficiency, the digital-food industry could reach $815 billion by 2030. If it skews the opposite way, it could grow slow to just $85 billion. For restaurants and other food providers, the growth-path picture could mean a 21 percent increase in industry revenue and a 12 percent decline for traditional grocers. If not, things will largely remain flat, slightly favoring grocery stores.

According to the research, the industry will see something in between.

The base case assumes strong growth to $365 billion, adding 8 percent to the food service revenue pull and sapping 3 percent from traditional grocers.

There’s a lot that goes into the UBS base case. Convenience is a big one, it takes time to cook and everyone claims they’re so busy they just can’t do it. Nearly half of survey respondents said delivery saves them time or they don’t have time to cook. (Reporter’s note: Netflix watchers consume 140 million hours of content per day. You’re not busy, you’re lazy!)

Respondents also said choice and quality were big factors in ordering digital delivery. If you want some great Pad Thai, you’re just not getting the best version making it yourself. And when a couple wants Pad Thai and enchiladas, they simply won’t cook both.

And maybe the most intriguing factor in all this is cost. It’s common knowledge that cooking at home is cheaper, but as digital delivery gets more efficient with overhead-slashing dark or ghost kitchens and robots delivering more, that common notion could change.

“…Taking a fuller ‘all-in cost’ approach, including the cost of time and the cost associated with owning/renting a kitchen and its equipment, we believe we are already close to cost parity between a home-cooked meal and a restaurant-delivered meal,” wrote UBS researchers. “Over the coming years, as the cost of restaurant-delivered food comes down, ordering in might become 25 percent cheaper than home-prepared food (on a total cost basis), and 40 percent cheaper in a scenario where drone delivery and professional kitchen automation drive down further the cost of delivered food.”

If digital delivery is suddenly a lot cheaper than cooking, it wouldn’t just be high-earning millennials “busy” with Netflix—it could be everyone.

According to our own survey with SeeLevel, the average order in Dallas was $25. If that were $15, even people who love to cook would be more willing to take a night or two off. And ordering two to three times a week, according to UBS, would put the food industry on course for the-kitchen-is-dead scenario.

UBS has a few choice stock picks for such a scenario. The best picks: Naspers, an Internet company and technology investor that has invested in several delivery companies, and Mail.ru, the Russian email provider that holds 80 percent of Delivery Club. The worst picks: Sun Art, a global food retailer, and General Mills, maker of a huge range of grocery goods.