How far has the ghost kitchen industry come? So far that there’s now a company built to address the pain points of the ghost kitchen industry.

Kristen Barnett founded Hungry House in New York City as a new take on ghost kitchens, one that was better for culinary innovators, higher quality for customers and more economical for the business with some notable tweaks to the format across the board. Barnett is among a handful of veterans in this ultra-convenience-focused food space exploring new models as the industry evolves.

She brings a lot of lessons from her time as chief operating officer at ghost kitchen operator and software developer Zuul. After Zuul was acquired by Kitchen United in October 2021, Barnett said she got right to work on the next project and honing her elevator pitch.

“Hungry House partners with up-and-coming chefs and culinary voices and other leaders that bring to life the most exciting new food. We do this by cooking those signature items from those chefs in our kitchen and featuring them on our web platform and in our kitchen for pickup and delivery,” Barnett explained.

Founder and CEO Kristen Barnett.

While the ghost kitchen space has found plenty of success with culinary megastars like Guy Fieri—or just mega stars like YouTuber Mr. Beast—Barnett saw a huge number of hip, emerging foodies adapting to the pandemic era. They built a following around their food ideas on social media and got that food to fans however they could.

“Fundamentally, what I look for is a proof of concept. Do they have a user base that is excited? Hungry House allows them to tap into that demand and monetize their hard work,” she said. “It’s an opportunity to expand their brand but also a way to actually monetize food without having to raise a ton of money to start a restaurant.”

Followers, so far, are not the same as financing. That’s where Barnett saw the opportunity: help these culinary visionaries and brand builders stick to their skills while Hungry House does just about everything else.

“We have a culinary team in the kitchen, they’re executing after an intensive onboarding. We do spend a significant amount of time ingesting them into our system, costing them out, identifying our supply chain partners, operationalizing them in our space and setting up the technology to execute,” said Barnett.

For the brand builders, they come up with the menu items and get a cut of the revenue. At that end, it’s a bog-standard licensing model.

Here’s how it’s ‘anti’

At first blush, Hungry House is another ghost kitchen with some neat features like a real counter in a heavily trafficked shopping center—but it’s still a ghost kitchen. When asked what was so “anti-ghost-kitchen” about the concept, Barnett said there were a few special ingredients: transparency, seasonality, quality and economics.

On the topic of transparency, Hungry House is certainly anti-ghost-kitchen. How many delivery drivers or customers were surprised that Pasqually’s came out of Chuck E. Cheese or that Just Wings’ wings were fried in Chili’s fryers? Barnett said she wants to be frank with consumers, and market directly to them about how the model is better.

“We wanted to create an organizing framework to communicate that we will be partnering with new chefs and new brands. We think about it like we’re doing a movie premier; how can we tell that story?” said Barnett. “It allows us to shine a light on our amazing supply chain partners and then when people ask where can you get this food, you can say Hungry House.”

That’s easier than saying, “search on your chosen platform and hope we operate in your market.”

That mantra dovetails with seasonality. The potential to swap in brands and foods is a unique strength of ghost kitchens, but almost as a plan B for when a delivery-only concept doesn’t resonate. Fried chicken didn’t work? Quietly swap in a burger brand and keep cooking. Barnett wants to be intentional about that swap.

“We organize our partnerships by season. Some of them will certainly transcend multiple seasons, that’s our goal, but at the same time it creates space for a brand activation that may only want to go for four months,” said Barnett.

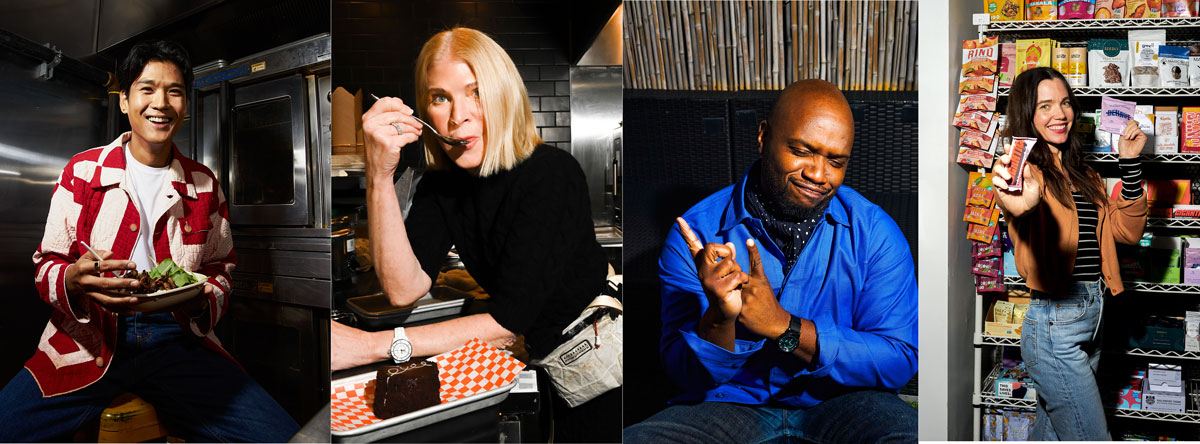

From left, Woldy Reyes, founder of Woldy Kusinal; Martha Hoover, creator of Apocalypse Burger; Food Sermon founder Rawlston Williams and Goods Mart founder Rachel Krupa make up Hungry House’s “season one.”

She said keeping the menus small and focused is critical for quality. Of the initial four partners, each have just three to five items on the menu. That keeps things simple in the kitchen but also means consistency for customers. Barnett looked to the wildly popular MrBeast Burger as evidence the ghost kitchen industry has some uniformity issues. The delivery-only chain has anywhere from two to three-and-a-half out of five stars on review sites in New York City, with issues around consistency in those mediocre reviews.

“I saw that the traditional ghost kitchen or virtual brand model has a lot of issues around quality control and scaling successfully,” said Barnett. “What we’re able to do is guarantee end-to-end control of the food and have a team that is focused on successful execution.”

The final pain point for Barnett is the economics. She points consumers to the Hungry House digital platform or the brick-and-mortar location, not third-party aggregators. That slims her operating cost significantly.

“If you’re opening up in a ghost kitchen, you’re going to have your rent, labor, COGS” or cost of goods sold, “then you have the 30 percent delivery commission that’s going to make it hard to work,” said Barnett.

Instead, she pays about 10 percent to a white label delivery provider and retains the customer for the next seasons.

Barnett said the company is initially focused on covering Manhattan and all its foodies. The first physical storefront opened in November in the Brooklyn Navy Yards; Barnett says traffic is strong, and orders are flowing for pickup and delivery. Customers are also keen to visit the location, browse the menu on a tablet and find something fun to eat, perhaps further evidence of the “anti” in Barnett’s ghost kitchen model.